Elizabeth Boleyn, Countess of Wiltshire

The Countess of Wiltshire | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | Elizabeth Howard c. 1480 |

| Died | 3 April 1538 (aged 57–58) |

| Buried | St. Mary's Church, Lambeth 51°29′42″N 0°07′13″W / 51.4950°N 0.1202°W |

| Noble family | |

| Spouse(s) | Thomas Boleyn, 1st Earl of Wiltshire |

| Issue more... | |

| Father | Thomas Howard, 2nd Duke of Norfolk |

| Mother | Elizabeth Tilney |

Elizabeth Boleyn, Countess of Wiltshire (born Elizabeth Howard; c. 1480 – 3 April 1538) was an English noblewoman, noted for being the mother of Anne Boleyn and as such the maternal grandmother of Elizabeth I of England. The eldest daughter of Thomas Howard, 2nd Duke of Norfolk and his first wife Elizabeth Tilney, she married Thomas Boleyn sometime in the later 15th century. Elizabeth became Viscountess Rochford in 1525 when her husband was elevated to the peerage, subsequently becoming Countess of Ormond in 1527 and Countess of Wiltshire in 1529.

Family and early life

[edit]Elizabeth was born c. 1480 into the wealthy and influential Howard family, as the elder of the two daughters of Sir Thomas Howard, later 2nd Duke of Norfolk, and his first wife Elizabeth Tilney.[1] Her paternal grandfather, Sir John Howard, was created Duke of Norfolk in 1483 by King Richard III.

Her family managed to survive the fall of their patron, King Richard III, who was killed at Bosworth in 1485 and supplanted by the victor, King Henry VII, when she was about five years old. Elizabeth became a part of the royal court as a young girl.[2]

Marriage and lady-in-waiting for the royal court

[edit]It was while she was at court, that she wed Thomas Boleyn, an ambitious young courtier, sometime before 1500, probably in 1498.[2] According to Thomas, his wife was pregnant many times in the next few years but only three children lived to adulthood. The three children were:

- Mary Boleyn, mistress of Henry VIII of England (c. 1499 – 19 July 1543).

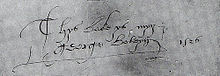

- George Boleyn, Viscount Rochford (c. 1504 – 17 May 1536).

- Anne Boleyn, Queen consort of Henry VIII of England (c. 1501/7 – 19 May 1536)

The other two boys were Thomas born 1496 and Henry 'Hal' born 1500. Both died of the sweating sickness plague during the outbreak in 1506.[citation needed]

Throughout this time, Elizabeth was a lady-in-waiting at the royal court; first to Elizabeth of York, and then to Catherine of Aragon. Based on later gossip, Elizabeth Boleyn must have been a highly attractive woman.[3] Rumours circulated when Henry was involved with Anne Boleyn that Elizabeth had once been his mistress, with the suggestion even being made that Anne Boleyn might be the daughter of Henry VIII.[4] However, despite recent attempts by one or two historians to rehabilitate this myth, it was denied by Henry and never mentioned in the dispensation he sought in order to make his union with Anne lawful. Most historians believe it is likely that this rumour began by confusing Elizabeth with Henry's more famous mistress Elizabeth Blount, or from the growing unpopularity of the Boleyn family after 1527.[5]

1519–1536

[edit]

In 1519, Elizabeth's daughters, Anne and Mary, were living in the French royal court as Ladies-in-waiting to the French Queen consort Claude. According to the papal nuncio in France fifteen years later, the French King Francis I had referred to Mary as "my English mare", and later in his life described her as "a great whore, the most infamous of all".[6]

In the words of historian M.L. Bruce, both Thomas and Elizabeth "developed feelings of dislike" for their daughter Mary.[6] In later years, Mary's romantic involvements would only further strain this relationship. Around 1520, the Boleyns managed to arrange Mary's marriage to William Carey, a respected and popular man at court. It was sometime after the wedding that Mary became mistress to Henry VIII (the exact dates as to when the affair started and ended are unknown), although she never held the title of "official royal mistress," as the post did not exist in England. It has long been rumoured that one or both of Mary Boleyn's children were fathered by Henry and not Carey. Some historians, such as Alison Weir, now question whether Henry Carey was fathered by the King.[7] Few of Henry's mistresses were ever publicly honoured, except Elizabeth Blount, who was mentioned in Parliament and whose son, Henry Fitzroy, was created Duke of Richmond and Somerset in an elaborate public ceremony in 1525.[8] Henry's relationship with Mary was so discreet that within ten years, some observers were wondering if it had ever taken place.[9]

In contrast to Mary, Elizabeth's other daughter, Anne, is thought to have had a close relationship with her mother. Elizabeth had been in charge of her children's early education, including Anne's, and she had taught her to play on various musical instruments, to sing and to dance, as well as embroidery, poetry, good manners, arithmetic, reading, writing and some French.[10] In 1525, Henry VIII fell in love with Anne, and Elizabeth became her protective chaperone. She accompanied Anne to Court, since Anne was attempting to avoid a sexual relationship with the King.[11] Elizabeth travelled with Anne to view York Place after the fall of the Boleyn family's great political opponent, Cardinal Thomas Wolsey – an intrigue which had given Anne her first real taste of political power. She was crowned queen four years later.

Elizabeth remained in her daughter's household throughout her time as queen consort. Tradition has it that Anne's daughter, Elizabeth I, was named after her maternal grandmother. However, it is more likely that she was named after Henry's mother, Elizabeth of York, although the possibility that she was named after both grandmothers cannot be ruled out.

Elizabeth Boleyn sided with the rest of the family when her eldest daughter, Mary, was banished in 1535 for eloping with a commoner, William Stafford. Mary had initially expected her sister's support (Anne had been Mary's only confidante within the Boleyn family since 1529),[12] but Anne was furious at the breach of etiquette and refused to receive her.[13]

Only a year later, the family was overtaken by a greater scandal. Elizabeth's younger daughter, Anne, and her only living son, George, were executed on charges of treason, adultery, and incest. Anne's two chief biographers, Eric Ives and Retha Warnicke, both concluded that these charges were fabricated.[14] They also agree that the King wanted to marry Jane Seymour. Beyond this obvious fact, the sequence of events is unclear and historians are divided about whether the key motivation for Anne's downfall was her husband's hatred of her or her political ambitions.[15] Despite the claims of several recent novels, academic historians agree that Anne was innocent and faithful to her husband. Nonetheless, the judges obeyed the King, condemning Anne, George Boleyn and four others to death. Elizabeth's husband Thomas Boleyn and brother Thomas Howard, 3rd Duke of Norfolk provided no help to the condemned. The accused men were beheaded by the axe on 17 May 1536 and Anne was executed by a French swordsman two days later.

Later life and death

[edit]Following the annihilation of the family's ambitions, Elizabeth retired to the countryside. She died only two years after her two younger children. Her husband died the following year. Elizabeth is buried in the Howard family chapel at St Mary's Church, Lambeth. The church, decommissioned in 1972, is now the Garden Museum.

Footnotes

[edit]- ^ Hughes, Jonathan (2007). "Boleyn, Thomas, earl of Wiltshire and earl of Ormond (1476/7–1539), courtier and nobleman". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/2795. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- ^ a b "The Life and Death of Anne Boleyn", by Eric Ives, p.17 (2004).

- ^ "Anne Boleyn," by Marie-Louise Bruce, p. 13 (1972).

- ^ 'Hart, Kelly (1 June 2009). The Mistresses of Henry VIII (First ed.). The History Press. p. 118. ISBN 978-0-7524-4835-0.

- ^ "The Life and Death of Anne Boleyn," by Eric Ives, p. 16 (2004).

- ^ a b "Anne Boleyn," by Marie-Louise Bruce, p. 23 (1982).

- ^ Henry VIII: The King and His Court, by Alison Weir, p. 216.

- ^ "The Six Wives of Henry VIII," by Alison Weir, p. 81 (1991).

- ^ "The Life and Death of Anne Boleyn," by Eric Ives, pp. 15–16.

- ^ "The Six Wives of Henry VIII," by Alison Weir, p. 148 (1991).

- ^ "Divorced, Beheaded, Survived: A Feminist Reinterpretation of the Wives of Henry VIII," by Karen Lindsey, pp. 58–60 (1995).

- ^ "Divorced, Beheaded, Survived: A Feminist Reinterpretation of the Wives of Henry VIII," by Karen Lindsey, p. 73 (1995).

- ^ "The Six Wives of Henry VIII," by Alison Weir, p. 273 (1991).

- ^ "The Life and Death of Anne Boleyn," by Eric Ives (2004) and "The Rise and Fall of Anne Boleyn," by Retha Warnicke (1989).

- ^ For the debate, see the introduction to J.J. Scarisbrick's 1997 edition of his biography "Henry VIII," "The Life and Death of Anne Boleyn," by Eric Ives, pp. 319–337 and "The Rise and Fall of Anne Boleyn," by Retha Warnicke, pp. 189–233 (1989).

Bibliography

[edit]- Block, Joseph S. (2004). "Boleyn, George, Viscount Rochford (c. 1504–1536), courtier and diplomat". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/2798. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- Cokayne, George Edward (1959). The Complete Peerage, edited by Geoffrey H. White. Vol. XII, Part II. London: St. Catherine Press.

- Head, David M. (2008). "Howard, Thomas, second duke of Norfolk (1443–1524), magnate and soldier". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/13939. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- Ives, E. W. (2004). "Anne (Anne Boleyn) (c. 1500–1536), queen of England, second consort of Henry VIII". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/557. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- Lindsey, Karen (1995). Divorced, Beheaded, Survived: A Feminist Reinterpretation of the Wives of Henry VIII. Reading, Maine: Perseus Books. Archived from the original on 28 June 2011. Retrieved 8 March 2011.

- Richardson, Douglas (2004). Plantagenet Ancestry: A Study in Colonial and Medieval Families, ed. Kimball G. Everingham. Baltimore, Maryland: Genealogical Publishing Company Inc.

- Weir, Alison (1991). The Six Wives of Henry VIII. New York: Grove Weidenfeld.